the portugal diaries, ep. 1: colares

the tiny but mighty Colares DOC, where indigenous grapes and rare terroir create strikingly powerful wines

Much to everyone’s chagrin, I have once again returned from abroad, and naturally it has ~changed~ me. Yes, I feel you rolling your eyes at me through the screen. No, it will not stop me.

In the spirit of harnessing this energy while it lasts, I’m compiling a short series of posts inspired by a few wine experiences on this recent trip, which was a 10-day jaunt through the Azores and mainland Portugal (Porto, Coimbra, Lisbon, and Setúbal). Over the coming weeks, I’ll be highlighting several of my favorite spots and new learnings, such as my changing thoughts on the role of conglomerates in winemaking, the wines of the Azores and why volcanic wines simply slap (Gen Z term alert), and whatever else I can think up.

But for today, let’s deep dive a bit into one of my favorite visits of the trip—Ramilo Wines—and how they showcase the power of the tiny wine region of Colares.

A bit of context

For the better part of the last 6 months, I’ve been planning to run a Global Study Tour for my 16 of my fellow Columbia Business School classmates through the Jerome A. Chazen Institute for Global Business to study “sustainability in agriculture”. Since the trip is now over, I can finally confess that this was a very thinly veiled attempt to spend my spring break drinking wine and get it paid for it. Sorry not sorry.

Now, if you’re reading this and doubting the validity of an MBA (which would be extremely fair), or, god forbid, are someone from the Chazen administration, rest assured we had a very studious and business-school appropriate time in Portugal. Our days ranged from spending two days with Sogrape Vinhos discussing wine marketing and supply chain challenges (very timely, thx tariffs), to meeting with sustainable textile entrepreneurs, to accelerating the ongoing egg shortage by consuming a veritable bakery full of pasteis de nata.

An inauspicious start

On Day 8 of 10 in Portugal, our humble squad escaped from a quick 12 hours in Coimbra only to find that the storm we had been miraculously out-running for the past four days in Portugal had finally caught up. On the two hour drive from Coimbra, the skies unleashed, threatening us with a slippery walk through the vines, and even forcing one of our upcoming winery visits in Setúbal to cancel.

Our destination was none other than Ramilo Wines — a fourth-generation, family-owned winery near Mafra and Sintra, roughly an hour northwest of Lisbon, with vineyard properties in the surrounding Lizandro River Valley (IGP Lisboa) and a few dozen kilometers away on the Atlantic coast in the DOC of Colares.

IGP and DOC are two levels of the EU standard classifications for wine regions, each with their own allowed grapes, winemaking restrictions, ageing requirements, and tasting boards that certify wines and allow them to be labeled as a certain region. More on this some other time.

We arrived to Ramilo’s winemaker, the indomitable Jorge Mata (Revista de Vinhos’ 2025 Revelation Winemaker of the Year), donned in muddied work boots and heavy-duty weather gear, doing his best impression of a airport tarmac worker, waving our minibus onto a rare patch of dry dirt at the end of the driveway next to the nondescript cellar door. A bit of grumbling and raincoat wrangling later, we unfolded from the bus, dodging raindrops and mud puddles to quickly gather in the cellar for Jorge to walk us through the Ramilo wines.

The vineyard and the story

Things quickly turned around with the turnaround story (haha get it) of Ramilo, explained by Jorge — which, for what it’s worth, is nearly as interesting as the wines themselves. Despite the fact that the winery is a fourth-generation family-owned and run establishment, the clear perspective of the brand are a recent development. Founded in the 1940s, Ramilo had become primarily a distribution and export house by the mid 2010s, in addition to manufacturing a fairly large quantity of generic wines from a wide array of grape varieties.

In the last decade, however, Jorge and the new generation of the family have recharged the brand with vigor, converting the vineyard sites to organic farming, replanting and focusing on grapes indigenous to the region (notably Castelão, Ramisco, Arinto, and Malvasia), and formalizing their low-intervention winemaking practices. They even went so far as asking producers in Madeira to send them cuttings of their vines to replant after genetic testing proved the Madeiran grapes were originally taken from the Colares region.

I can only imagine how that conversation went. maybe:

‘hey madeira can you give us our grapes back’

‘wdym, these are our grapes’

‘no, science says you took them from us’

‘oh damn ok mb bro here’s some sticks’

or maybe not.

While this shift in vision is recent, the effect is clear — Ramilo’s wines tell an intentional and compelling story of a heritage producer revitalized with local winemaking traditions, pushing the boundaries with experimentation, and championing sustainability.

The wines

Ok enough prattle let’s get into it.

Oohhhhhh baby. I hope I’m not mistaken in saying this was one of the most unique tastings I’ve had in a long time, and one that made every damp sock in the cellar worthwhile.

In total we tasted through seven Ramilo cuvées — four that are bottled under the IGP Lisboa classification, and three that are bottled under the stricter DOC of Colares label. The IGP Lisboa region is especially notably for its so-called “Atlantic influence”, which proved to be some of the group’s favorites of the whole trip, overdelivering on expectations with a potent concoction of acid, salt, fresh fruit, and floral notes.

If you find yourself wondering anything like ‘why on earth is saltiness in wine desirable??’ and ‘what even does that even taste like??’ I’m going to have to defer that discussion to a later post as well, but for now just imagine the pure drinkable deliciousness of the salt lassi (the criminally underrated sibling to the mango lassi) somehow made its way into your local Sauvignon Blanc.

My personal standout in the first half was the Castelão, a punchy, tart raspberry, herb, and rose assault on the senses, made partially from grapes grown in Colares and partially from those in the broader Lisboa IGT. It landed on the palate with the perfume of a Barolo, the fresh crunchy fruit of a Beaujolais cru, and the age worthiness of a savory red Burgundy.

The second half of the tasting, on the Colares DOC wines, showcased the range of winemaking options possible with grapes grown in the unique Colares terroir. Colares is notable for its un-grafted vines, cultivated low to the ground, on sandy cliffs that overlook the Atlantic Ocean. Originally several hundred hectares, the DOC has shrunk due to a combination of real estate development and erosion, leaving a meager 50 acres under control of a handful of producers.

The proximity to the Atlantic requires vines in DOC Colares to be trained low to the sandy soil, to avoid excessive wind and retain heat. The well-draining, low-nutrient sandy soil is what ultimately limits the ability for phylloxera, a notorious vine pest, to grow, allowing for the cultivation of un-grafted vines (more on this later). It also yields grapes with strong flavor concentration and powerful acidity making the wines great candidates for ageing. In fact, heritage Colares producer Viúva Gomes’ wines are often aged for over 10 years by the producer themselves, and their 1934 Ramisco cuvée is allegedly still kicking around at over 90 years old.

(If anyone would like to roll the dice on one of these old Ramiscos for me, my birthday is coming up. I’ll send you my address.)

Colares DOC wines can only be made from Ramisco for the reds and from Malvasia do Colares, one of the seemingly millions of versions of Malvasia out there, with some small blending allowances, for the whites. The Ramisco performed with it's characteristic measured power, but I was partial to Ramilo’s quinquennial (apparently, the term for once every 5 years) Malvasia cuvée released in 2023. The unique blend combines Malvasia wines made across several different harvest years that are aged in a solera-like process under a layer of yeast known as flor in sherry production. The end result is a taste-defyingly complex wine with tertiary flavors not dissimilar to Jura Chardonnays, but with an unmatched level of fresh acidity, saltiness, and citrus.

On the rarity of “un-grafted” vines

I’ve used this word a lot, I recognize, and the meaning may not be obvious. I’ll imitate Jorge’s apt recognition that he was losing some of our group during the tasting and pause for a brief explanation of the term.

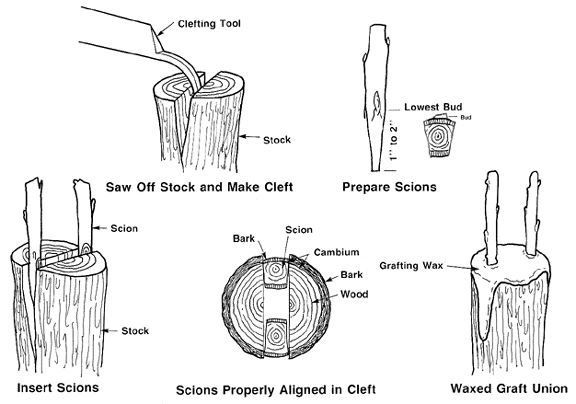

The (semi) short version is that in the mid-to-late 19th-century, an insect pest known as phylloxera, originally native to North America, rampaged through Europe, destroying nearly 90% of the continent’s vines. With no known cure, phylloxera eventually forced winemakers to replant their entire vineyards using a technique known as grafting.

Grafting (which could have a whole series of its own) is essentially when a North American species of vine (referred to as the stock), which has evolved resistance to phylloxera, is planted directly into the soil. Then, a more desirable, grape-yielding European species of vine (known as a scion) is artificially attached to the stock. The net effect is a vine with roots that are resistant to phylloxera, but yield the European species of grapes. Today, only about 2% of vineyards in Europe have avoided phylloxera and remain planted with un-grafted vines, and one of them is Ramilo’s site in Colares.

For those who don’t spend a ridiculous amount of time poring over wine region maps or reading articles on grafting techniques, a wine tasting made from un-grafted grape vines is roughly equivalent in rarity to acquiring tickets to a one-night only Eras Tour revival that somehow also includes Reputation (Taylor’s Version), all for the much more palatable price of 10€. (No, this post is not sponsored)

Final thoughts

I’ve said it once and I’ll say it again — go and find yourself some Colares wine, and if you can’t find any (which may be the case), please use this as inspiration to taste something new to you.

I hear some phrases all the time — “I only drink Sauvignon Blanc” or “Red wine is too heavy” or “I’m looking for a chilled red or a funky orange” and while I’ll always defend the idea that every wine has its right to exist, this experience reminded me that variety needs to be sought out and celebrated, even for the most experienced of wine drinkers. I (and most of the other trip participants) had never heard of Colares before planning this visit, and certainly had not tasted wines made from Ramisco, Malvasia do Colares, or Castelão, and look at me now, happily singing its praises. I’m sure this theme will return, but it bears repeating every time it comes up — wine, like many things, thrives in diversity. Go seek it out.

Beyond providing an introduction to an exciting something new in Colares, the Ramilo tasting was inspiring to hear the dreams and potential of those in the winemaking industry with a pure sense of purpose and humble origins. In under a decade, Ramilo has completely transformed from mostly unrecognizable bulk wine to premium, purpose-driven elegance, all while retaining a characteristic sense of heritage and respect for history that is notable of some of the best wines in the world. All in all, if the future looks anything like what Jorge has in mind, I’ll be drinking up.

Shoutout to Naama Laufer at NLC Wines in Brooklyn for putting me in contact with Ramilo! And a big thank you to Jorge Mata and Nuno Ramilo for coordinating our visit. Hit them up if you’re in the area.